It always felt paradoxical to me that we train machine learning models with billions of parameters using simple scalar objectives like mean-squared error or cross-entropy loss. How can something so complex be reduced to a single fitness score? Yet, the results seem to defy this reductionist approach.

Imagine if this would be the case for the other complex mechanisms that we know exist. Do we think that it is reasonable to assign a single number to the performance of the human brain? Could we meaningfully distill the essence of intelligence, creativity, and sympathy of a human into a single number and come up with a perfect mixture of these values so that minimizing this mixture would lead to the “optimal” performance? Imagine assigning Mahatma Gandhi a score of 2.764 and Lionel Messi a 2.845 on a “universal human performance index”. Only in computer games do we see phrases such as “Game over. You died and your score is 413.”

The stock market is another example of a complex system that defies simple quantification. The overall market state is defined by an intricate dance of market sentiment, micro and macroeconomic trends and geopolitical events that can hardly be summarized using a single score. While we use indices like the S&P 500 or the Dow Jones Industrial Average to gauge the overall performance of the market, these numbers hardly capture the full story.

The same could be said for ecosystems, weather patterns, or any other complex system we encounter. Attempting to distill their intricacies into a single, all-encompassing metric seems not only reductive but also potentially misleading. It ignores the rich interactions and emergent properties that make these systems so fascinating and unpredictable.

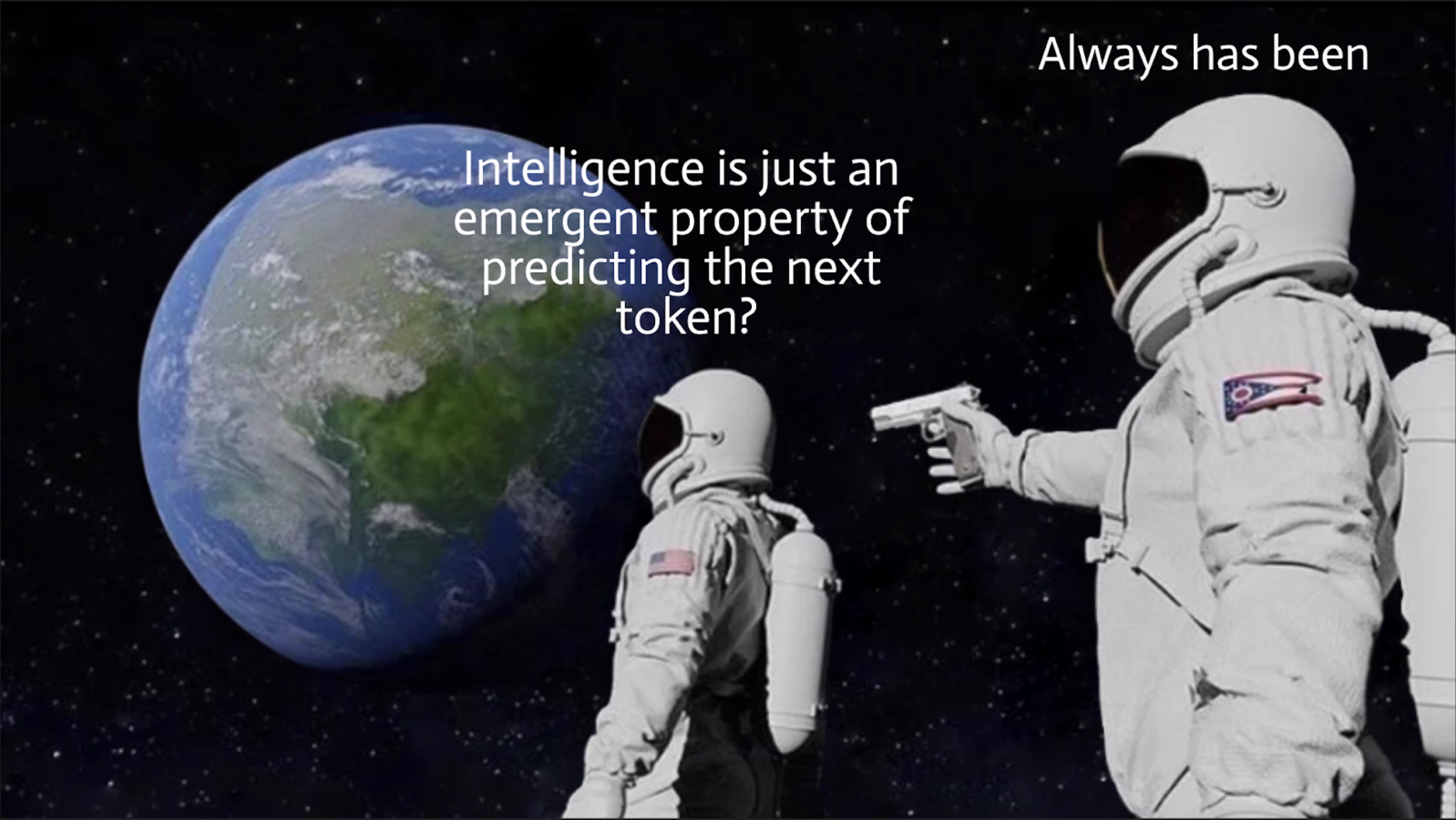

However, the success of machine learning models suggests that there might be something powerful about this simplification. Take large language models (LLMs) as a prime example. Their objective function is simple: predict the next word based on the given context, minimizing the probability of error. So, how come language models demonstrate such a surprising versatility in different domains, from code generation and poetry composition to translation and scientific reasoning? It's as if they've stumbled upon a secret formula for intelligence, hidden in plain sight.

Of course, it is not entirely true. On the model evaluation side, the practitioners often care about a combination of different metrics and often adjust the data mixture, curriculum learning and different regularizations to achieve a certain effect on the metrics. However, at the end of the day, the model is trained to minimize just a solitary number that encapsulates its overall fitness.

Let’s consider another example of a complex system: the evolution of life on Earth. From the primordial soup of chemicals, this process has given rise to an astounding diversity of organisms we see today with amazing adaptation mechanisms to pretty much any environment we see here on Earth. It has a staggering complexity, spanning countless generations over a hundred years timeframe to make any perceptible change in adaptation. Yet, the mechanism that leads to this complexity is relatively simple: adapt or perish. Organisms that are better suited to their environment survive and pass on their genes, while those that fail to adapt fade into extinction. This mechanism is actually relatively straightforward, especially compared to the complexity of the organisms that it produces. It does not dictate the specifics of each adaptation.

Instead, they are emergent properties that arise as organisms strive to achieve the evolutionary goal of survival. The specific adaptations an organism develops are a result of the complex interplay between its genetic makeup, its environment, and the random mutations that occur over generations. This interplay gives rise to the incredible diversity and complexity we see in the natural world, from the intricacies of a respiratory system, or the precise shape of a flower's petals.

While there are some nuances, it won’t be a huge exaggeration to assume that the success of evolution as a whole on the planetary level could actually be summarized with a single metric of planetary adaptation: how well have organisms adapted to the environment they live in? This shows that there exists a complex large scale system governed by a simple, straightforward rule, but results in great complexity.

What is interesting is that, while this objective has clearly improved from the beginning of time, it has not monotonically increased, nor has it been increasing linearly over time. For example, it might just be that some time during the Cambrian explosion, the creatures were more adapted to the environment than the current generation of Earth dwellers. Also, curiously, In some specific instances creatures seem to defy the very rules of evolution that created them. They might deplete their own resources, destroy its habitat by overpopulation or overconsumption, or choose not to reproduce at all (e.g. some humans or animals in captivity).

All that it is saying is that if the creature has an option to develop a mechanism (or get rid of an existing one) that would help it thrive better in its environment, this creature is more likely to adopt it.

Is it possible that this analogy to evolutionary systems can be extended to our modern foundational systems as well?

I believe that for Large Language Models, the analogy to evolutionary systems holds remarkably well, particularly when considering the phenomenon of in-context learning. The simple, seemingly myopic objective – predicting the next word or token – acts as a powerful evolutionary pressure. To consistently succeed at this task across the vast and varied landscape of human language, knowledge, and reasoning encoded in its training data, the model cannot rely on simple memorization or static patterns alone. It must develop internal mechanisms, or "adaptations," that allow it to interpret and utilize the immediate context effectively. In-context learning, therefore, emerges as a crucial adaptation. It represents the LLM's ability to, metaphorically, "read its environment" – the specific prompt or preceding text – and adjust its behavior accordingly. Just as an organism must adapt its survival strategies based on whether it finds itself in a resource-rich or resource-poor environment, or facing a predator or potential mate, an LLM must adapt its predictive strategy based on the instructions, examples, style, or factual constraints provided in its input, its "informational environment."

This adaptation is not explicitly programmed into the model. Instead, it is the most effective strategy to emerge from the optimization against its simple objective. To successfully predict the next word in a vast corpus of human-generated text—spanning everything from legal contracts and scientific papers to poetry and computer code—a model cannot rely on simple statistical correlations alone. It must become a master of context. It must infer grammatical rules, recognize stylistic patterns, identify factual relationships, and even grasp abstract concepts, all from the preceding text. This is the essence of in-context learning: a dynamic, on-the-fly adaptation to a new "environment" presented by the user's prompt.

This resolves the paradox we started with. The simple objective of next-word prediction does not directly define intelligence, creativity, or reason. Rather, it creates the selective pressure for these qualities to emerge as necessary components of a successful survival strategy. The model isn't "told" to be a poet or a programmer; it learns that to minimize prediction error across its entire training set, it must develop a generalized capacity to understand and manipulate symbols, logic, and style. In-context learning is the mechanism for this adaptation, allowing the static, pre-trained network to perform dynamic, sophisticated tasks. The simple objective, therefore, doesn't reduce complexity; it fosters it, proving that sometimes the most intricate systems can arise from the most humble of beginnings.